We have a thing for firsts. Be it the first human being to climb the Mt. Everest, the first to set foot on the moon, or any such feat, they leave an indelible mark in our collective consciousness. The ones who come second, even though achieving an equally significant accomplishment, often fade from our memory. One such second is the X-10 Graphite Reactor, the second artificial nuclear reactor after the Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1).

Before we take a look at X-10, we have to understand the circumstances in which it came about. The authorisation of the Manhattan Project by the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II meant that scientists began their research and development to produce the first nuclear weapons. In December 1942, CP-1 became the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor as the experiment led by American-Italian physicist Enrico Fermi achieved the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

Need for plutonium

While CP-1 was a success as a scientific experiment and showed that nuclear chain reactions could be controlled, it was built on a small scale, which meant that recovering significant amounts of plutonium wasn’t feasible. As plutonium, a transuranium element that had been recently discovered, was seen as a potential ingredient for atomic weapons, producing it for research was a priority.

The X-10 Graphite Reactor was thus born as an experimental air-cooled production pile that would help in designing the full-scale helium-cooled reactors that were also being planned. Whereas the X-10 Pile or Clinton Pile was to be built at the Oak Ridge site, the latter was planned to be constructed at Hanford. DuPont company was roped in to work with the University of Chicago to design and build both these reactors.

Less than a year

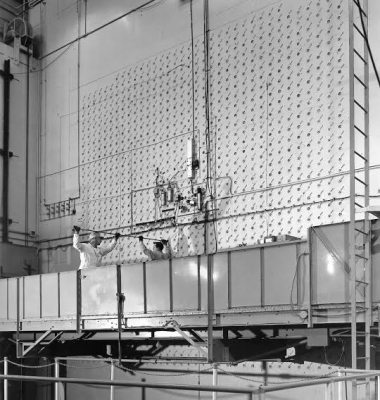

Even though the design wasn’t completely ready, DuPont went ahead with the construction of the reactor in early 1943. The X-10 was to be a massive graphite block (24-ft cube), protected by concrete and having 1,248 horizontal channels that were to be filled with uranium slugs surrounded by cooling air. The face of the pile was to be used to push new slugs into the channels, while irradiated ones fell into an underwater bucket at the rear.

These buckets of irradiated slugs were left to undergo radioactive decay before being moved to a separation facility , where remote-controlled equipment were used to extract the plutonium. Racing against time, the construction of the reactor was completed in less than a year.

On November 4, 1943, the X-10 went critical for the first time. This meant that the number of neutrons being produced were equal to the number of neutrons being absorbed, which in turn produced the same number of neutrons. A reactor thus operates in a steady-state when it becomes critical. By the end of November, X-10 started producing small but significant samples of plutonium, which were experimentally valuable.

Important learning

Even though it was decided that water should be used as a coolant for the Hanford reactors while X-10 was still under construction, X-10 provided important results and learning. The X-10 suppled the Los Alamos National Laboratory with the first significant amounts of plutonium, fission studies in which influenced the bomb design. The engineers, technicians, safety officers and reactor operators who worked on X-10 gained great experience, which they were able to apply once they moved to Hanford.

Once the war was over, the reactor was put to use for peacetime efforts, producing radioisotopes, utilised in industry, medicine and research. It remained in operation until 1963, when X-10 was shut down permanently. By 1965, the X-10 Graphite Reactor was designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. government and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Recognised by the American Chemical Society as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in 2008, the control room and reactor face are still accessible to the public through tours provided by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Picture Credit : Google