When returning from their famed moon mission in 1969, the astronauts of Apollo 11 returned with samples, including rocks, from our natural satellite. For decades after that, the only new material from space that geologists looked at came from meteorites reaching us. It was only in 2006 that a spacecraft sent material, including cometary and interstellar dust, back to Earth.

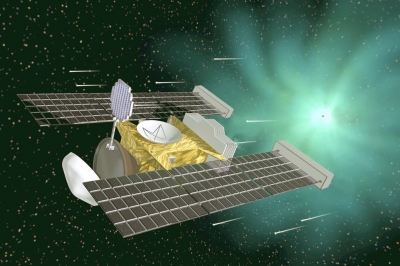

The Stardust mission was the first one to send back cometary samples and extraterrestrial material that came from outside the orbit of our moon. Launched in 1999, the Stardust spacecraft consisted of two solar arrays along with a sample return capsule that weighed 46 kg. It carried dedicated scientific and engineering instruments, which included the Cometary and Interstellar Dust Analyzer (CIDA), Dust Flux Monitor Instrument (DFMI), aerogel collector grid and navigation camera.

Substance called aerogel

Of these, the aerogel dust collector was of particular interest. The substance called aerogel was responsible for collecting the comet and interstellar dust. A silicon-based solid with a porous, sponge-like structure, it largely comprised empty space. Such a configuration enabled it to capture particles with minimum changes due to heat or chemical alteration, something impossible with conventional collection materials.

Before heading to the comet whose samples the spacecraft was scheduled to collect, it first visited an asteroid, 5535 Annefrank (named after Anne Frank, the Dutch-German diarist whose writings were published as The Diary of a Young Girl), in 2003. Flying within 3,300 km of the asteroid and clicking images of it, the flyby was seen as a preliminary run of what lay ahead for Stardust.

Wild encounter

By December 2003, Stardust was near its destination, comet 81P/ Wild, commonly known as Wild 2 (named after Swiss astronomer Paul Wild and pronounced “vilt 2”). It extended its tennis-racquet shaped collector, and after collecting all the material that was possible, sealed it in a vault in the re-entry capsule. It clicked a number of photographs as well and made its closest approach to the comet on January 2, 2004, flying within 250 km.

Two years later, in January 2006, Stardust released its conical capsule into the Earth’s atmosphere. The descent was stabilised by releasing a drogue parachute when 32 km out and the main parachute of the capsule opened up at a height of three km. After it touched down in the Utah desert helicopters arrived at the scene, picked up the capsule and transferred it to NASA’S Johnson Space Center in Houston within a couple of days. The search for signs of tiny little particles comic and interstellar dust – in the aerogel soon began.

What’s next?

Stardust, which was placed in hibernation after this phase of the mission was marked completed on January 16, 2006, got a new lease of life with an extended mission. Funding allowed for New Exploration of Tempel 1 (NEXT). after NASA’S Deep Impact had successfully observed the comet Tempel 1 in 2005 and also crash landed a probe on it.

The Stardust-NEXT mission was to continue mapping the comet and study how the impact crater changed. It reached its second comet target, Tempel 1, on February 14, 2011. While it became the first spacecraft to visit two comets in the process, Tempel 1 became the first come to be visited by two spacecraft.

The images and samples returned by Stardust helped us better understand comets, allowed researchers to discover a new class of organics more primitive than those found in meteorites and also helped identify irregular particles known as calcium-aluminium rich inclusions (CAIs) that are among the oldest solar system particles. A handful of interstellar particles too have been discovered and the search for more is still ongoing. Stardust’s extended mission ended on March 25, 2011 after which the spacecraft continues to orbit the sun. According to NASA’s predictions, it will never get closer than 2.7 million km to Earth’s orbit.

Ready to search for interstellar dust?

The sample returned by the Stardust spacecraft not only contained particles of various sizes collected from the comet Wild 2 but also rare and tiny interstellar dust particles.

While there are thousands of particles from the comet, the number of particles of interstellar dust are expected to be only in the 10s.

While this makes them incredibly rare and precious, it also makes the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack look easy.

As the search for interstellar dust would probably take researchers and scientists several years if they alone are involved in it they have started a Citizen Science Project Standust@home to crowdsource the search.

Through this project, they are seeking the support of talented volunteers from across the globe. If you are interested, you can also participate. You would. however, have to go through a web-based training session and pass a test before qualifying to register and participate.

If a volunteer discovers an interstellar dust particle, they appear as a co-author on scientific papers announcing the discovery, and also get the privilege of giving the particle its common name. Even if not that lucky, there is a ranking system based on the amount and quality of searching done with the top-ranked volunteers invited to visit the lab in Berkeley, the U.S.

Picture Credit : Google