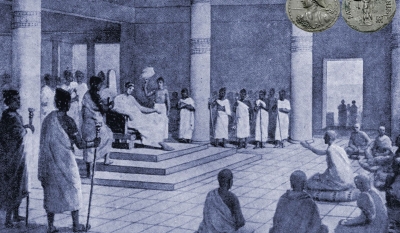

“King Milinda by name, learned, eloquent, wise, and able; and a devoted and faithful observer. Many were the arts and sciences he knew- holy tradition and secular law; philosophy; arithmetic; music; medicine; the four Vedas, the Puranas, and the Itihasas; astronomy, magic, causation, and magic spells; the art of war; poetry. And as in wisdom so in strength of body, swiftness, and valor there was found none equal to Milinda in all India. He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.” – On the Indo Greek King Menander, from the Milindpanho

After Alexander’s death, his vast empire (stretching from Greece to north-west India) was carved up amongst his generals. One of them, Seleucus, ruled over much of the Near East. By the 250s BCE, Bactria (Balkh in Afghanistan) had broken away, forming the Greco-Bactrian kingdom.

By 180 BCE, with the collapse of the Mauryan Empire, the Bactrian Greeks moved south of the Hindukush into India, under the ruler Demetrius. Various Greek dynasties ruled over parts of India till the 1st century BCE and are known as the Indo-Greeks. They were then defeated by the Scythian and Parthian invaders. We know about them mostly through the many different coins they had issued with their names.

Raid upto Pataliputra

One of the most important Indo-Greek rulers was Menander (155- 130 BC). Menander was born not in India, but up north in Greco-Bactria. He started out as a king there, but extended into the Indian subcontinent, ruling over the northern parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Punjab. His capital was a Sagla, a bustling city in northern Punjab, near modern-day Sialkot.

He raided upto Pataliputra. The scholar Patanjali and the Yuga Purana mention that ‘after having conquered Saketa, the Yavanas (Greeks), wicked and valiant,’ reached ‘The thick mud-fortifications at Pataliputra’. A great battle followed with ‘tree-like engines (siege engines).’

The Greek geographer Strabo wrote that he “conquered more tribes than Alexander the Great”, though this may just have been flattering exaggeration! He was also a great patron of Buddhism, and is referred to as King Milinda in Buddhist texts. He seems to have been not only a great soldier, but a keen thinker and avid debater.

FAMOUS DEBATE AND CONVERSION

The story of his conversion to Buddhism is interesting. Amusingly, according to the Milindapanha (“Questions of Milinda”), it is said that there were no scholars left in his capital as he would roam about engaging them in debate and defeating them, afterwards sighing, “No one speaking for any religion can defeat me in argument; alas for the world!” A Buddhist monk Nagasena showed up to debate with him. This debate recorded in Milindpanha which consists of questions supposedly asked by King Menander, employing Greek logic, to which Nagasena replies on the basis of Buddhist doctrine, with Indian reasoning. At the end of the book, King Menander is impressed, and adopts is impressed, and adopts Buddhism. The book is quite an intriguing and unexpected glimpse of the clash between Eastern and Western thinking.

KING ON ONE SIDE, GOD ON THE OTHER

Many coins have been found from Menander’s reign, and they are fascinating. You see classically Greek-looking coins, with the king in a variety of warrior poses on one side of the coin, and various Greek gods and Goddesses such as Athena, the goddess of wisdom, on the other. These coins could be straight from Greece! But, there is a difference. The inscriptions are bilingual, in both Greek and the native Kharoshti scripts. Later coins substitute the goddess Athena for various animal motifs, especially those important to the Buddhists, such as the elephant, bull and boar. There is even a coin with the eight-spoked Buddhist Wheel of Dharma. Imagine, a native Greek king, called Menander I Soter “The Saviour”, who most king Milinda for his Buddhist values!

Plutarch, a Greek biographer, relates that he died in camp while on a military campaign, and that his remains were divided equally between the cities to be enshrined in monuments, probably stupas, across his realm. After his death in 130 BC, he was probably succeeded by his wife Agathokleia who ruled as regent for his son Strato I. The last Indo-Greek kings were ultimately defeated by the Shakes by 50 BCE.

Picture Credit : Google