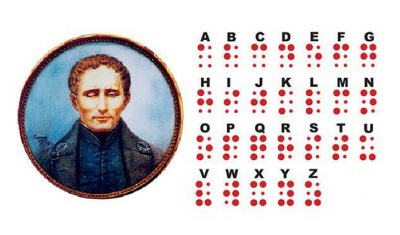

In 1829, a French population census listed 15-year-old Louis Braille, a pupil at the Paris Institute for the Young Blind, as `unable to read or write’. Yet in the same year, the young Braille published a new `language’ which provided the key to reading and writing for blind people.

He devised a completely new alphabet —a code of raised dots (which are much easier to feel and identify than a continuous line). The dots are arranged in domino-like combinations to form characters that correspond with letters of the alphabet, punctuation marks and common words such as ‘and’ and `the’.

The Braille ‘language’ is touch-read by running the tips of one or two fingers over the embossed text. In 1932, more than 100 years after the system was first published, Braille was adopted as the standard language for the blind in the English-speaking world. The original, 63-character, letter-by-letter system has since developed into a more advanced, contracted form in which the dot symbols represent common letter combinations such as ‘ow’, `ing’, and ‘ment’, making it quicker to read and write, and less space consuming. Now there are Braille adaptations for every major language in the world, and for music, mathematics and science.

Braille can be ‘hand-written’, using a stylus to press out the dot characters onto a sheet of paper clamped into a metal frame. The writer works on the back of the sheet, from right to left, so that when the paper is turned over the dots are raised, and read from left to right in the normal way. Braille typewriters and computers with Braille print-out facilities are in common use, and the printers’ latest embossing machines can imprint both sides of a single sheet of paper without the dot patterns on either side conflicting.

Braille is used mostly by people who are born blind or who lose their sight at an early age. Many people, however, become blind in their 60s, after many years of reading conventional print — and may also because of age, diabetes or arthritis, have reduced sensitivity in their fingers. For them, the adaptation to touch-reading dotted symbols can be difficult. Some depend totally on taped books. Others learn to touch-read the alternative ‘Moon, system of raised letters — the stronger, simpler outlines reflect standard letter shapes, and are easier to learn.

Invented in England in 1847 by Dr William Moon of Brighton, Moon’ is a letter-by-letter system with nine basic characters, whose interpretation depends on which way up or round they are used The lines of text are read alternately from left to right and then from right to left, in a continuous flow. Moon is used in the English-speaking world only, and is much less established and versatile than Braille. The range of texts is limited. as printing technology responded more readily to embossing the dotted characters of Braille than the Moon lines and circles.

Picture Credit : Google